Towards Velotopia

Imagine a city where you never need a car. No matter where you live everything you need is within an easy bike ride.

Shops, your place of work, friends, family and entertainment is all only a short ride away, with your journey covered the entire way to shield you from the sun and protect you from the rain. The building where you live would even be designed with ramps to easily allow you to roll to street level, and large lifts to get you back up to your apartment.

Transportation would be cheaper, far more energy efficient, and potentially faster. Saving the world and helping citizens to keep fit and active all at the same time.

This daring new vision of a city of the future is "Velotopia", and one of the world's leading thinkers around the concept is the University of Canberra's own honorary appointee Dr Steven Fleming.

Author of the internationally acclaimed book Cycle Space, Dr Fleming has presented to a range of prestigious architecture forums around the world, and has appointments with universities around the world including Harvard and Colombia. As director of Cycle-Space International, Dr Fleming consults with governments, developers, fellow architects and designers to promote cycling as a mainstream mode of transport.

We recently spoke with Dr Fleming to learn more about Velotopia, and how the university campus of the future can be designed to encourage cycling for staff and students.

Q: Why is it important that cities move towards a focus on planning around cycling?

A: Most of the world's population can't afford to use cars, but when they do (because for other reasons we are wanting to lift the world out of poverty) the world's energy consumption is going to go through the roof.

But here is the problem: in the five-million-plus population category, conurbations like Dallas-Forth Worth with their incredible networks of freeways are providing better average commute times than cities like London or Singapore that rely more on public transport. If you're in charge of a boom town in the developing world, of course you're going to start building freeways and encouraging car use and sprawl.

The challenge then is to devise an alternative model of urban growth, that we ourselves, in affluent cities, choose over freestanding houses connected by freeways.

My design research work is underpinned by the hypothesis that a purpose built bicycle city would save people time in their day.

We see the truth of that in small cities like Amsterdam and Copenhagen. I see my role as using design modelling to show the superiority of a bicycle mobility platform for cities of five-million-plus.

Few cities around the world promote cycling like Amsterdam (image courtesy Flickr)

Q: Can you give an overview of the type of research you are conducting?

A: Methodologically you would call it research by design but because of my own background in academia there is a good deal of critical discourse analysis to what I do also.

In my case research by design means working through hypotheticals, asking what an undulating ground plane would look like if its purpose was to help cyclists get up to speed or slow down, asking how far shops should be apart if people were riding rather than walking or driving between them, seeing if it's faster to ride down an apartment building with spiralling access than walk to a lift then go to the basement and get in a car.

Critical discourse analysis comes into play because everything I just mentioned rubs against some cultural bias or urban design dogma, so it becomes important to go back and scrutinise that discourse from a new critical stance, that of bicycle advocacy.

Q: What is "Velotopia"?

A: Advocates of transit oriented development have crystalline models to refer to like Howard's Garden City diagram. Advocates of the polycentric car city have fictitious proposals like the Futurama exhibition from the 1939 World's Fair or Frank Lloyd Wright's Broadacre that they can refer to. The walkable city too has its models, medieval walled cities for instance.

In each case the advocate has a model providing them with the rules and objectives of a kind of a game. Bicycle planning lacks a similar model.

All we have are cities designed for the horse, where the bike has been used as modern alternative. I'm thinking of historic town centres in the Netherlands in particular, but let's never forget that they were not built for cycling so are hardly ideal.

They also tell us nothing about how big a bicycle city might get, or how it might put cycling on an equal footing with modes that protect us from rain. It's important at this stage in history to conceive an ideal model of a bike-centric city, so we know what we're striving for with bike planning.

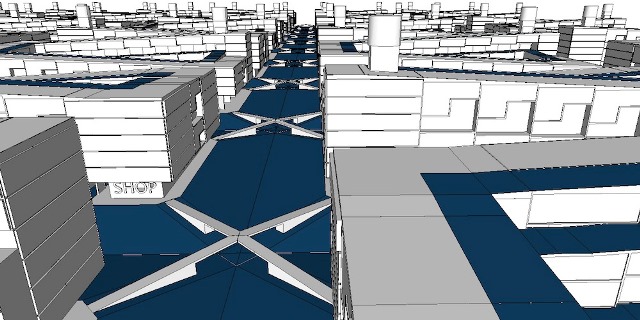

The city of the future? A concept image of Velotopia (image courtesy Cycle-Space)

Q: In a dream world for you, what would the perfect city of the future look like?

A: If ever some megacity grew from the outset according to the Velotopia model it would be flat, dense, permeable, car free, provide grade separation between people on bikes and people on foot, have ride-inside buildings, be no larger than around 15km in any direction and have canopies to protect cyclists from rain.

Most cities have histories spanning the age of walking and horses, then the age of the electric streetcar and the train, and finally the age of private automobiles. Streetcars and cars produced many urban districts where cycling may never be mainstream because of the gradients and the sprawl. However, the pre-twentieth century districts would certainly fair better if bikes were outnumbering cars—which is what the Europeans are aiming for with their cities now.

But there's another kind of space in our cities that I haven't mentioned: our former industrial areas. These could be redeveloped according to a bike centric model. They tend to be large and flat and they are interlinked via waterways and rail routes. So really, they're perfect!

I have difficulties with planners who take a one size fits all approach to every district and see motorists, cyclists and patrons of public transport blended like dye in a glass. To my mind cycling should generate cyclespace, by which I mean other spaces (heterotopias) that are more like wax in a lava lamp in the way they relate to the rest of the city.

The future of the family car? A Dutch bakfiets cargo bike (Image courtesy Flickr)

Q: How can modern apartment developments in cities be better designed to incorporate and promote cycling?

A: You wouldn't build a bike friendly apartment as an end in itself. You would do it to give city dwellers, especially those raising children, the same conveniences they would have if they had a car and a house in the suburbs. In the suburbs you can drive your car filled with groceries and a baby asleep in a capsule into your house and close the garage door to the world.

I raised my kids in a terrace house and could do exactly the same thing only with a cargo bike (Dutch bakfiets). But there's a problem with a city of terrace houses and that is that it can't grow without trains, and the problem with trains is they lead to a city with overall slower commutes than a city of freeways.

What I've found is you can have the compactness of Manhattan and the convenience of the terrace house, if rows of terraces are arranged in 5 to 10 storey coils. You might take your cargo bike up in an oversize lift, but leaving the building would simply be a matter of letting go of your brakes and winding your way to the ground via a continuous spiralling access gallery.

Q: How can universities incorporate and promote cycling to and on their campuses?

A: The kind of building I just mentioned would be ideal for student housing.

All of the car parks should be turned into more student houses, or in the short term into gardens for the students to eat from.

University planning attests to theories and values held by thinking people of our grandparents' time. So leave the history department with a car park outside, but update the rest so it reflects what we teach in the classroom about climate change and public health. If you want the short answer, it's ban everybody from driving.

Q: What are the biggest challenges around moving cities towards a cycling focus?

A: I've never won the heart of someone who doesn't use bikes for transport, or changed the mind of someone who wasn't in all the top classes in school. So I seek audiences with smart people in power who are already cycling for transport themselves.

A bicycle parking garage in Holland (Image courtesy Wikimedia)

Q: Are there any great examples of cities incorporating cycling into planning?

A: On one front, Canberra is a great city. When your civic leaders saw research pointing to barrier protected bike lanes in city centres, they built them. They didn't use cyclists as a proxy for minority groups that are harder to bash.

Minneapolis is a standout example for the way they're building new apartments facing an old train line through the city that has since been turned into a cycling and jogging route.

New York is exciting, because it's a bellwether city that has just reengineered a lot of its avenues to reduce driving and increase cycling.

But let's face it, 99% of best practice around bicycle planning comes out of the Netherlands. That's even the case with my own work. Most of my talks and the press I've received has been in the Netherlands, and of course it was the Netherlands Architecture Institute Publishers that picked up my book.

Words by Daniel Murphy and Stephen Fleming. Main image courtesy Cycle-Space