Community Connections

Making end-of-life care more inclusive for the LGBTQIA+ community

An end-of-life journey can often be filled with the fear of discrimination for the LGBTQIA+ community – those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and asexual, or others who identify as having diverse sex, sexuality, or gender.

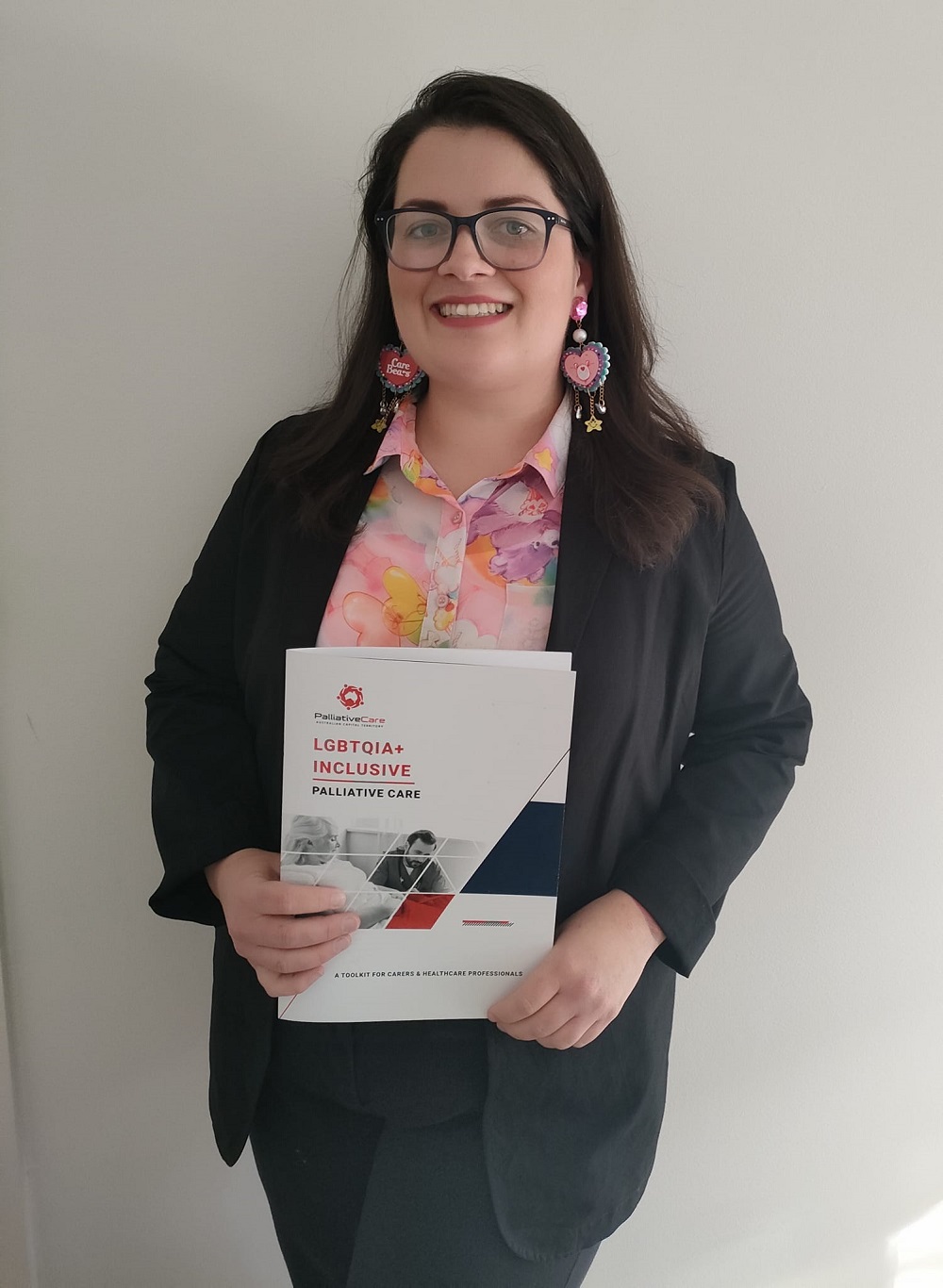

Community-based charity organisation Palliative Care ACT has been looking at ways to deliver care in a more inclusive way, calling on University of Canberra Lecturer in Nursing, Alicia Hind, to help develop a toolkit designed to better understand the needs of LGBTQIA+ people who have a life-limiting illness.

Alicia hopes that instead of worrying about discrimination due to gender identity, sexuality, bodily diversity or different family and relationship structures, people will instead feel safer accessing care when they need it.

“It’s all about starting conversations that otherwise aren’t had, and healthcare is a little bit behind in this area,” Alicia says.

“When we look at paediatrics for example, we’re taught to not say ‘mummy and daddy’ because we shouldn’t assume that everybody has that kind of family at home. At any time in a person’s life, we need to consider that they might have other people at home who are important to them.”

The toolkit is a 20-page document designed for health workers, volunteers and carers .

“There are also sections in there for people from LGBTQIA+ communities themselves and how they can find out more information, what organisations might help them to receive better care, what they can expect and the questions that might be asked,” Alicia says.

Alicia has drawn from lived experience as part of the LGBTQIA+ community, her expertise as an aged care nurse and through her work as an academic, where she is completing a PhD about the experiences of LGBTQIA+ people in nursing homes.

“Coming from an aged care background I’ve seen the generational differences and when it comes to healthcare in general, my wife and I have not had great experiences, especially in getting care that is accepting of all your identities,” Alicia says.

She says a big part of the toolkit is the importance of inclusive language.

“Making changes to language doesn’t discriminate against anybody else, it actually opens a conversation to more people. I think that’s always the fear, that people will lose things by giving more opportunity to minorities, but they won’t,” Alicia says.

“Everywhere we look, language tends to be heteronormative and cisgendered, particularly when you’re filling out intake forms for medical care.”

The word ‘heteronormative’ refers to the concept that heterosexuality is the preferred or ‘normal’ mode of sexual orientation; ‘cisgendered’ describes a person whose gender identity and sex assigned at birth are the same and is the antonym of ‘transgender’ – these terms are part of a glossary of LGBTQIA+ language included in the toolkit.

Alicia says the terms will help healthcare workers to ensure interactions with a patient and their loved ones are more inclusive, from the start.

“I think this could make people feel safer to access care at the appropriate time, so it could mean more timely intervention and possibly people getting better access to pain relief and end-of-life information and options,” Alicia says.

Palliative care itself often carries a stigma more broadly, as being associated with impending death – which can make some people with a life-limiting diagnosis hesitant to seek it out.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) says that worldwide, it is estimated only one in 10 people who need palliative care are receiving it.

It argues that palliative care improves the lives of patients and their families and should be seen as a human right.

The Palliative Care ACT toolkit is seen as a step in the right direction for inclusive end-of-life care, while there is more work to be done to provide a safer healthcare environment and a more inclusive society.

“There’s an assumption that since the marriage equality vote in 2017 everything’s ok, but there’s still a lot of discrimination on a daily basis for people.”

“It’s important to understand and recognise where your privilege sits, and that working in healthcare is a position of power and you need to use that for good.”

The toolkit can be accessed here.

Words by Emma Larouche, photos: supplied.