Ideas, Progress & the Future

Rise of the Machines … Onstage

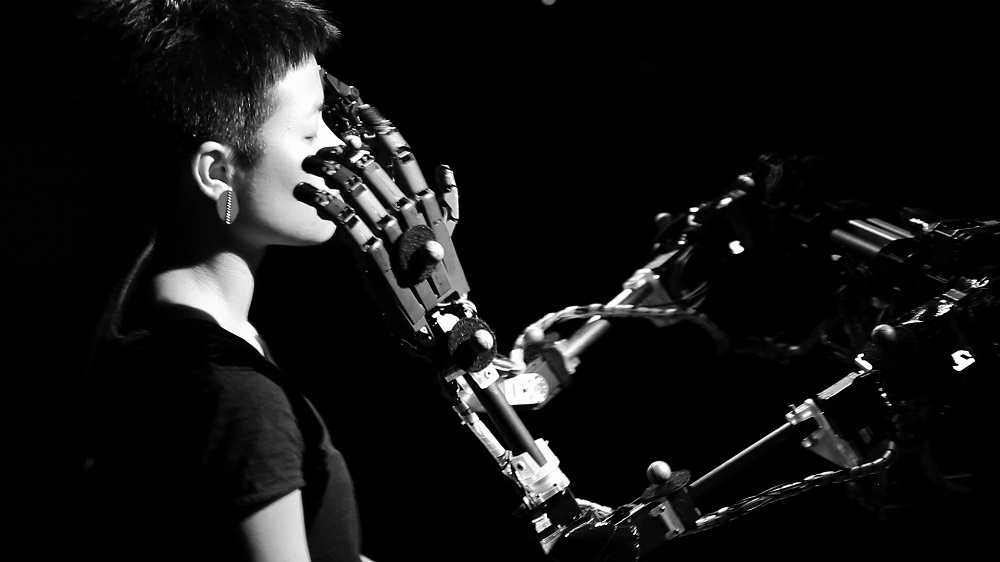

There’s a moment in Bill Vorn and Louis-Philippe Demers’ robot dance performance Inferno, when audience members – who have been strapped into upper body exoskeletons – realise that issues of control and dominance may not be as simple as they initially assumed.

“Inferno takes this dystopian impression of a cold, hard exoskeleton that mechanically controls your movements, and then transforms the experience into a playful, communal and enjoyable experience,” says Associate Professor Elizabeth Jochum.

“At the moment that they start to work together with the robot, the audience members author their own experience, and enter into a new, intimate relationship with technology.”

Elizabeth believes that as robots are increasingly integrated into daily life, the theatre is also growing in prominence as a testing ground to observe human–robot relationships, to develop a deeper understanding of human–robot interaction – and ultimately, to build better robots.

A Visiting Fellow at the University of Canberra, Elizabeth is from the Research Laboratory for Art and Technology at Aalborg University in Denmark. She has spent over a decade working at the intersection of art and technology around the world, traversing the spaces where robotics transmutes theatre – and transforms audiences.

The theatre has always been a laboratory, she says – experimentation lies at the core of what theatre makers do. Introducing robots into this framework, where artists and engineers collaborate and look at how humans and robots interact, is a meaningful way to understand how technologies shape human experience.

Theatre lies in closer proximity to real life than movies or television, because it is performed in front of a live – and captive – audience.

“It’s a beautiful testing ground, to experiment with the current level of available technology, and to consider the aesthetic, ethical and philosophical implications of our robotic future in a communal space,” Elizabeth says.

“The audience experiences something together, reflects on it together. And then tied to that experience are the larger questions of our values, what it means to be human – this is traditionally what theatre performances are built around.”

This is important when considering how and where robots will develop, for example in health care or education.

“In the movies, you can do a lot with CGI, which is further removed from lived human experience,” Elizabeth says. “But with real robots – motors overheat, batteries die, and the corporeal relationship between human performer and robot is to scale.”

“Interacting with an embodied, physical robot in the real world affords a different kind of interaction – it is ultimately more effective at changing people’s attitudes, perceptions and beliefs.”

But why is it even necessary to grow knowledge and explore human–robot relationships?

“From factory floors to assistive devices for everyday living, robots are here,” says Elizabeth. “And yet, a lot of people are still not clear about the differences between real and fictional robots, what’s actually possible now and what we’re still just dreaming about. There seems to be a gap between where we think the tech is, and where it actually is.”

Looking behind the curtain to understand the truths of robotics, mulling questions of autonomy, agency and ethics, are particularly important because public perception shapes public policy.

“For most people, interactions with robots are still pretty rare," Elizabeth says. "This is why it is so important to provide opportunities for people to interact with robots directly and deepen their own understanding of technology."

“Humans are very willing to imbue objects with life, it’s how we ascribe agency,” Elizabeth says. When it comes to robot performers, audiences are also good at coming up with their own explanations for a particular behaviour or movement.

“If there’s cognitive uncertainty, an artist/performer can leverage the suspension of disbelief in a theatre setting to tell a story, while having the audience fill in any gaps … and so become part of the performance itself.”

Combine the potential for this kind of interaction with the ability to create characters, and playwrights, choreographers and designers have a lot to contribute to the creation of robots that are compelling, engaging and social. Building relationships, shaping perceptions and observing interactions in a theatre setting can also ultimately influence better robot design.

As comfort levels are an important consideration in technological design, Elizabeth has conducted a study on audience preferences and expectations of both mechanoid and humanoid robots.

“We found that post-interaction, the audience’s ideas and attitudes had changed – where initially they thought they would prefer a humanoid robot, they ended up feeling more comfortable with a mechanoid robot.”

Larger questions of gender, race and disability must also figure into the design discussion, and can be sparked via performances.

“Robots are frequently designed around normative assumptions, and I see opportunities for more nuanced discussion of representation, especially concerning gender and race, in robotics. Theatre can help with that,” Elizabeth says.

“Technology should be inclusive and empowering – we need to be careful of generalisations, and work more on a case-by-case basis.”

Firmly convinced that more studies in the wild – out among people – are needed in order to shape our understandings of human–robot relationships. Elizabeth co-founded the Robots, Art, People and Performance (RAPP) Lab with UC’s Associate Professor Damith Herath.

“We believe it is important to test robots in environments where there is lots of ‘noise’, ie people moving, talking, living, and we also believe in the tremendous value that artists bring to the discussion,” she said.

Last May, RAPP Lab embarked on a project with Questacon in Canberra, in which they asked people to draw with a robot.

“The robot was actually an industrial robot arm, the kind you would see in a factory,” Elizabeth says. “It was capable of different types of movement – some were more functional and ‘robotic’, while with other people, the arm moved in a more fluid, expressive way.”

“The important thing about this experiment was that it happened in the world, and people were interacting with the robot on a task that they were invested in. That is essential for understanding how people naturally interact with robots, and interpret their behaviour.”

It was an installation that underscored Elizabeth’s firm belief that the first step to implementing robots is to first understand the people who will interact with them. RAPP Lab's activities advocate for this "human-centered" approach to studying robots.

The robot performances Elizabeth has worked on range in context from more traditional theatre productions to improv festivals. But the audiences all have something in common.

“If audiences are coming to a show that incorporates robots, there tends to be a predisposition to engage with the ideas that the technology is proposing,” she says.

“And always, the question is asked: how do we imagine our future with robots? What new possibilities can we envision?” … even as that future is, knowingly or unknowingly, imagined in a darkened theatre.

In addition to her research and work in robotics in theatre, Elizabeth is working on building yet another bridge; her current book project, Deus Ex Machina: Robots on Stage in the Second Machine Age, surveys the field of robot performance across theatre, dance, opera and visual art to see how artists contribute to envisioning "new possibilities for what might be”.

Words by Suzanne Lazaroo.

Photos by Julia Spicina, Zane Cerpina, Barnabás Várszegi and Louis-Philippe Demers

Inferno by LP Demers and Bill Vorn (© 2015)

The Blind Robot by LP Demers (© 2013)

The Dynamic Still by Elizabeth Jochum (© 2017)