Community Connections

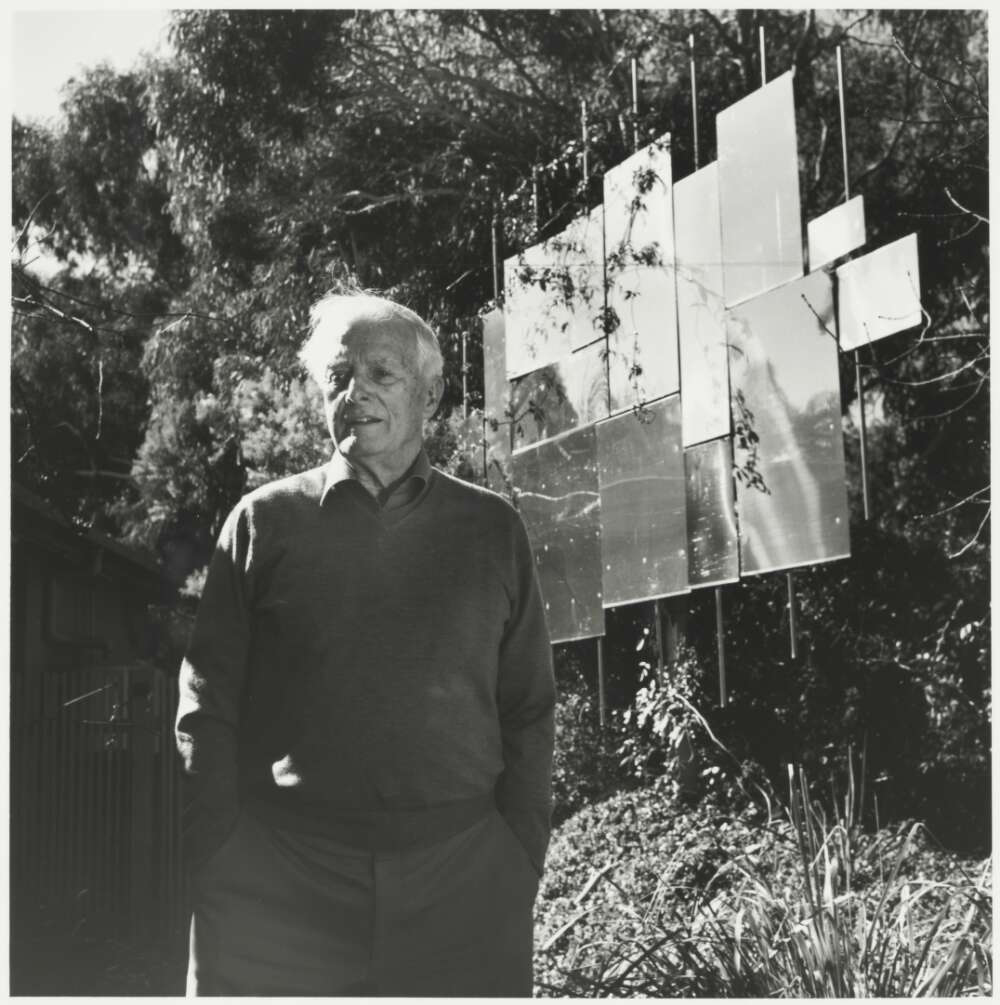

Vale Derek Wrigley, 16 February 1924 – 22 June 2021

To log in to his computer, Derek Wrigley OAM typed ‘D-E-S-I-G-N’, says his son Ben.

It was the perfect password for someone who believed that design was key to solving every problem on the planet.

The trailblazing architect and designer passed away late last month at 97, after living and breathing a design philosophy, career and practice spanning over 70 years.

“Just a month before he passed on, he was redesigning his own hospital bed, so that he would be more comfortable,” Ben says.

A prominent figure on the Australian design scene, Derek’s design commissions range from the Reserve Bank of Australia to the Academy of Science to the National Capital Development Commission, and far beyond.

Canberra was home, and it brims with the practical works of his imagination – and often, his dexterity. Both a dreamer and a doer, he built many of his own designs, including the Commonwealth Coat of Arms in Court 3 of the High Court of Australia, which he constructed from copper rods in 1980.

Derek created industrial and street furniture – a particular interest during his two decades with the Design Unit at the Australian National University (ANU) – and buildings which were ahead of their time. He designed landscapes, solar devices and sculptures, and fashioned graphics and logos. And this is hardly an exhaustive list.

The funny thing about design though, says Ben, is that it can be so ubiquitous and invisible at the same time.

“Who thinks about how well a street sign works?” he says. “My father did so much great work, but he didn’t necessarily say it was his. I remember someone saying that he ‘hid his light under a bushel’, because he was so humble.”

As entrenched as his work is in Canberra’s design bedrock, Derek’s contributions are also inexorably woven into the fabric of its community.

He was an active member of the Canberra Art Club, and a founding member of the Craft Association of the ACT (which is now Craft ACT), Wood Group of the ACT, Inventors Association ACT and the Design in Education Council.

Derek was a leader in the design world not just for the quality of his designs, but for his vision of building a better world.

“… it is not so much about designing things but finding social ways of improving society for the better, by discussion, education and creating awareness of unrecognised ways that are missing that could improve all our lives,” Derek wrote, referring to what he termed ‘social design’.

In 1979, he became one of the founding members of the ACT Branch of Technical Aid to the Disabled (TADACT, its name now changed to Technology for Ageing and Disability, its scope expanded). To this end, he conscripted many of his designer contemporaries to create solutions to improve the lives of disabled people, all in a volunteer capacity.

Annabelle Pegrum AM first crossed paths with Derek in the 1980s, because of his work with TADACT.

Now an Adjunct Professor and a Member of the University of Canberra Council – as well as the former UC Architect – Annabelle was at the time providing consultancy services for an initiative supporting independent living for people with disabilities.

“It was a very new concept then,” she says, recalling that the TADACT group were unique in what they made possible with their innovative design work.

“Derek was ingenious, in the way he would apply industrial design intelligence – the items he designed did not look ‘special’ or different, they were simply well-designed that items anyone could use.

“I was always in awe of Derek – few people at the time were involved with this particular kind of work, and fewer still could do what he could.”

Derek later established TAD Australia to link up the state chapters and served it in various roles. For his work with TADACT, he received a Medal of the Order of Australia in 1989.

Derek was also a Fellow of the Australian Institute of Architects (AIA), a Life Fellow of the Design Institute of Australia (DIA) and an associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects.

In 2014, the AIA introduced the annual Derek Wrigley Award for Sustainable Architecture, in homage to his passion for sustainable design.

The visual expression of a philosophy

Derek designed the University of Canberra’s distinctive logo, which dates back to its earlier incarnation as the Canberra College of Advanced Education (CCAE).

Fascinated by logos, Derek saw them as “a visual expression of the philosophy of a particular institution”.

When the CCAE commissioned Derek to design its insignia in 1969, he came up with a logo that was representative, simple and effective, and which reflected his minimalist aesthetic.

The logo was composed of five linked Cs, representing the fields of science, technology, art, administration and commerce (SS Richardson, Parity of Esteem: Canberra College of Advanced Education).

When the CCAE became the University of Canberra in 1990, the five Cs shifted in meaning, to represent its faculties instead.

“This showed just how successful it is as a logo, to be so adaptable – you wouldn’t get that kind of longevity unless something worked very well in the first place,” says Bill Green, Emeritus Professor at UC.

Bill met Derek on the Canberra design scene in the 80s, joining him in TADACT work.

“Derek was such a prominent figure on the design scene, and we got along very well – we had similar views on design, for one thing,” Bill says. “He was particularly passionate about and advanced in sustainable design, and he raised that idea with me.”

At the time, Bill was in charge of the basic design course at the CCAE. “I got him to come in and give lectures for the students – he was always very engaging,” he says. “Derek was very interested in education, and in how we talked to budding designers.”

In his eyes, it was important to lay the groundwork for good work from future generations.

“I admired him enormously and learned much from him,” Bill says. “He was so passionate and committed, and he could do just about anything – that’s how good he was.”

A man who could do anything

“For my father, the world was his oyster and he seemed to feel there was nothing outside the realm of possibility,” Ben says.

“Derek was trained as an architect, but he built houses on his own too – it wasn’t till I built my own house, that I realised that the average architect does not build his own designs!”

This can-do perspective extended beyond the realm of the professional, and into the personal for Derek.

“When he was about 65, he went abseiling over a cliff in a wheelchair!” Ben says. “He was able-bodied himself, but was out with a group of disabled people, and decided to also have a go.

“In so many ways, my father was fearless.”

Born in Lancashire, England, Derek initially failed his high school certificate … after an apprenticeship, he went on to study architecture at the Manchester College of Art (now the University of Manchester), and ranked first in the country in the 1945 architectural exams.

In 1947, Derek moved to Australia, with £100 in his pocket.

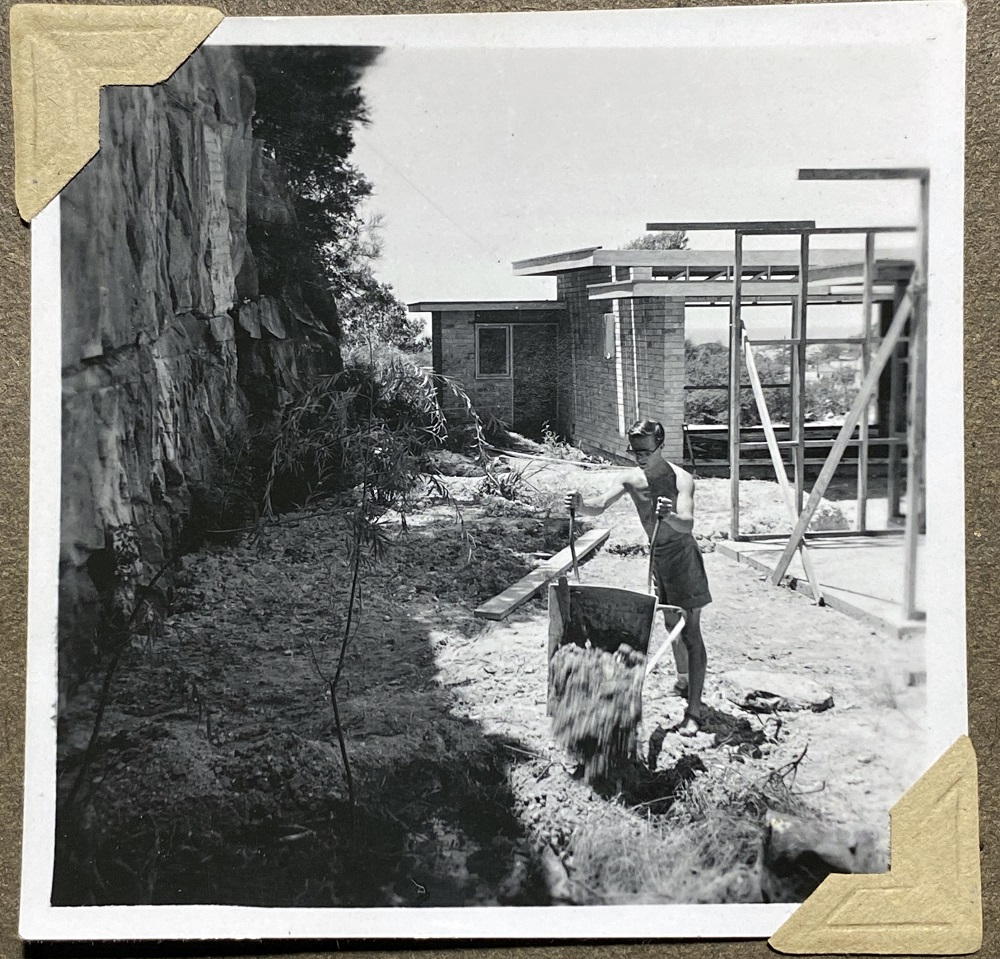

“This was a phenomenal amount of money at the time, and the first thing he did was buy a sandstone quarry in Sydney and build a house, then another,” Ben says. “This young man, from a tiny little town, who had never trained in construction, arrived in vast Australia and began building his first two houses, OB1 and OB2, in Sydney.”

In 1954, Derek married Hilary Archer, and the second of the two houses he had built so far became their home.

While immersed in his building work, Derek also worked with an architect firm in Sydney, and taught architecture at the Sydney Technical College and University of Technology (now the University of New South Wales).

Derek’s influence on the national design scene can be seen even in those early days.

In 1953, he became a founding member of the NSW Chapter of the Society for Designers for Industry, an early precursor to the DIA; he also founded the Industrial Design Council of Australia three years later, together with his contemporary Fred Ward.

Fred invited Derek to move to Canberra in 1957, to take on the role of Assistant University Designer at the ANU. After a break to take on commissions at the Reserve Bank of Australia and the National Library of Australia, Derek returned to the ANU as University Designer and Architect.

Canberra also became the site of Derek’s third owner-built house, OB3, in which Ben and his brothers Simon and Adam, grew up. Derek was always ahead of his time, an early adopter of new technologies and ideas, and the house is hailed by the Australian Institute of Architects as an “outstanding building for its time”.

“As a child, I remember my father was always talking about materials – about the qualities of wood, glass and stone – so I ended up with an extraordinary sense of tactility myself,” Ben says.

“Someone asked me recently, how it is that I can fix so many things – it’s because I break so many things. My father taught me the limits of different materials – it is this tactility that lets one know how far one can push a material.”

Derek also taught Ben how to evaluate and see light and space – today, Ben is an architectural photographer.

While building his fourth house – OB4 – Derek was also conducting restoration works on Byrne's Mill in Queanbeyan; the historical building housed his architectural practice. It was also where he set up The New Millwrights a non-profit advocacy group focusing on sustainable home design and energy use.

In 1980, Derek married Maxine Davies. They lived in OB4 – this structure marked Derek’s first major foray into what became a huge passion for him – solar passive design, which relies on greenhouse principles to trap solar radiation, thereby saving energy.

When Derek began building work on his fifth house, it was with Ben working alongside him. House Five and Six were built by both Ben and his wife, Sarah Houseman – the sixth, project managed, is the EcoSolar House in Chifley.

“When we were building together, I’d often find him working with pen and paper onsite, perhaps drawing a junction between one wall and another and seeing how they were to be connected – not everything is in the plans, he’d say!” says Ben.

When Derek and Maxine moved to a townhouse in Mawson in 1991, it was the first time since he got to Australia that Derek was living in a house he hadn’t built.

His interests had expanded from designing and building solar passive houses to adapting existing houses to better improve energy use – the Mawson house became his testing ground and Derek retrofitted many innovative concepts to use renewable energies, and to be more energy efficient. His first book grew out of this work – Making Your Home Sustainable (2004) is now in its fifth edition.

His father never had a day off, Ben says – so retirement proved more academic than actual.

“Just before he went into hospital last month, he asked me: do you have any problems for me to solve?” Ben says. “That’s just who he was – always looking for something to do, something to fix.”

Derek spent his later years as he had spent the preceding – thinking, writing and working towards his hope “for an increasing understanding of its corollary of awareness by society that design has tremendous power for good in everything we as humans try to do”.

“In this way design as a verb must logically lead us toward sustainability – a direction toward better design to satisfy real needs we cannot afford to ignore on a finite planet.”

Words by Suzanne Lazaroo. Self-portraits by Derek Wrigley, provided by Ben Wrigley.