Co-developing a new approach to media literacy in the attention economy

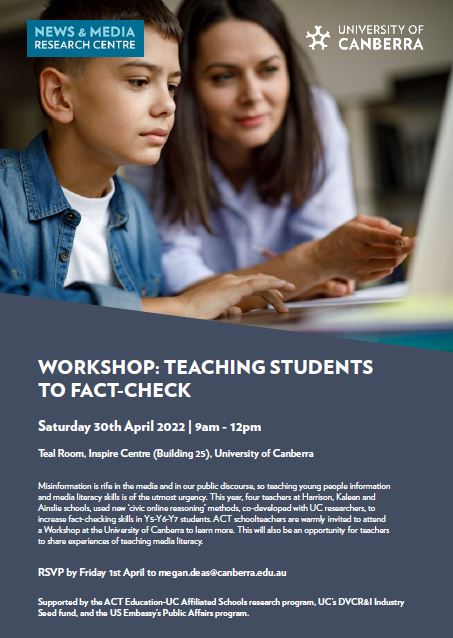

NEWS - WORKSHOP: TEACHING STUDENTS TO FACT-CHECK

When: 9am - 12pm, Saturday 30th April 2022

Where: Teal Room, Inspire Centre (Building 25), University of Canberra

To register: Email megan.deas@canberra.edu.au

Misinformation is rife in the media and in our public discourse, so teaching young people information and media literacy skills is of the utmost urgency. This year, four teachers at Harrison, Kaleen and Ainslie schools, used new civic online reasoning methods, co-developed with UC researchers, to increase fact-checking skills in Y5-Y6-Y7 students.

ACT schoolteachers are warmly invited to attend a Workshop at the University of Canberra to learn more. This will also be an opportunity for teachers to share experiences of teaching media literacy.

- Teachers will learn to apply ‘civic online reasoning’ in their English, HASS and Media Arts classrooms.

- Civic online reasoning can be taught and learned at any age, but the target group in this workshop is Years 5-7.

- Civic online reasoning (McGrew et all, 2017, 2018) recognises the importance of the Internet as a source of information, and of being in possession of accurate information when debating social and political issues.

- Civic online reasoning also focuses on action: not what students know, but the steps they take to verify information.

- UC educators will lead participants through engaging, interactive scenarios that have been co-created with ACT educators. The aim is to instil fact-checking ‘reflexes’ in students – i.e., when should one check the veracity of a claim?

Chief Investigators

- Associate Professor Mathieu O'Neil, University of Canberra

- Dr Rachel Cunneen, University of Canberra

- Mr Reece Cheater, Harrison School

- Mr Wayde Margetts, Ainslie School

- Ms Michelle O’Brien, Harrison School

- Ms Kelly Turner, Kaleen Primary School

Funding

Co-developing a new approach to media literacy in the attention economy – Part 1

Funders: ACT Education Directorate - Affiliated Schools Research Program Funded Project & Deputy Vice-Chancellor Research and Innovation Industry Collaborative Research Grant

CIs: Cunneen, O'Neil, Cheater, Margetts, O’Brien, Turner

Co-developing a new approach to media literacy in the attention economy – Part 2

Funder: Embassy of the United States Public Affairs Program

CIs: O'Neil, Cunneen

Resources

- Rachel Cunneen, Mathieu O'Neil (2021, 5 Nov.) Students are told not to use Wikipedia for research. But it’s a trustworthy source. The Conversation.

- Civic Online Reasoning, Stanford University.

Background

Summary

Instilling in young people ecosystem-appropriate media literacy skills is of the utmost urgency. The digital media environment is saturated with a multiplicity of claims, some of which are dubious, whilst others actively seek to disinform. In the so-called attention economy time is precious, and deep engagement with dubious claims is a poor strategy, as it represents a waste of time better spent elsewhere. Instead, students should acquire the means to quickly decide which claims are worth their attention. We address a concrete question – how do primary and secondary school students interact with fact-checking practice – and also raise a societal issue: should the epistemological principles underlying Wikipedia editing be mobilised to combat conspiratorial thinking? This project innovates because of the age of our subjects and because we use Wikipedia as a fact-checking tool, challenging negative perceptions of its reliability.

Traditional media literacy approaches

Traditionally, online literacy methods included a checklist of website design clues, with questions people might ask themselves when initially arriving at a webpage including: ‘Does this webpage look professional? Are there spelling errors? Is it a .com or a .org? Is there scientific language? Does it use footnotes?’ These questions are no longer proof of reliability: anyone can easily design a professional looking webpage and use spellcheck; a ‘.com’ or ‘.org’ URL (or the use of footnotes) does not always guarantee content credibility; and the use of scientific language does not always reflect levels of expertise.

Should we then rely on critical thinking skills by searching for logical fallacies? No: when solicitation is constant and the online ecosystem is awash with claims of unclear veracity, deep engagement is a poor strategy when confronted with content that expertly mixes the real with the fake. One could spend hours untangling these strands, wasting time best spent dealing with reliable information (Caulfield 2018, Warzel 2021).

Yet digital media literacy is a core competency for engaged citizenship in participatory democracy (Mihailidis & Thevenin 2013) and the need for a significant increase in media literacy programs in schools is clear. Recent studies (Notley & Dezuanni 2019, 2020) have shown that Australian schoolchildren are not getting nearly enough media literacy education: ‘Just one in five young Australians said they had a lesson during the past year to help them decide whether news stories are true and can be trusted. (…) We believe young people should be receiving specific education about the role of news media in our society, bias in the news, disinformation and misinformation, the inclusion of different groups, news media ownership and technology’ (Notley & Dezuanni 2020). We are sympathetic to this call for increased critical media literacy regarding bias in the news and the impact of ownership on shaping media content. However, incorporating critical themes into the school curriculum runs the risk of being perceived as a politically partisan endeavour, and of being rejected by some stakeholders.

Lateral reading and Wikipedia

When confronted with a dubious claim, an effective strategy is to ‘think like a fact-checker’ (Wineburg & McGrew 2018). In practical terms, this means that one should not engage directly – instead, the best way to learn about a source of information is to leave it and look elsewhere. Underlying this ‘lateral reading’ is the principle of civic online reasoning which emphasises action: not what students know, but the steps taken to verify information (McGrew et al. 2017). Civic online reasoning is quick, thus nullifying the ‘attention’ issue, and its focus on source reliability is non-partisan. From there, our project innovates in two ways.

Firstly, media and information literacy researchers typically aim to examine and/or increase the fact-checking capacities of high school and university students. However, research conducted in 2018 by the Australian e-safety commissioner found that out of 3,520 parents surveyed, 81% said that their preschool children already spent time online. In this group, 94% reported that their child was using the Internet by the age of four. Teaching media and information literacy to high-school students therefore leaves this vital instruction much too late.

Secondly, educators are accustomed to warning students against citing Wikipedia as a primary source as ‘anyone can edit it.’ In fact, popular articles are reviewed thousands of times, so edits are based on ‘reliable sources.’ All modifications to an article, and any disputes in the article’s ‘Talk’ page, are archived on the website: the editorial process is transparent. Apart from a few infamous exceptions, such as the Croatian Wikipedia which was hijacked by far-right activists (Wikimedia 2021), Wikipedia projects have remained neutral, and reliable: it is virtually impossible for conspiracies to be published, or remain published.

References

- Caulfield, M. (2018, Dec. 19) Recalibrating our approach to misinformation. Digital Learning in Higher Ed.

- McGrew, S., et al. (2017). Can students evaluate online sources? Learning from assessments of civic online reasoning. Theory & Research in Social Education, 46(2), 165-193.

- McGrew, S., Breakstone, J., Ortega, Teresa., Smith, M. & Wineburg, S. (2018) Can Students Evaluate Online Sources? Learning From Assessments of Civic Online Reasoning. Theory & Research in Social Education, 46:2, 165-193, DOI: 10.1080/00933104.2017.1416320

- Mihailidis P. & Thevenin B. (2013). Media literacy as a core competency for engaged citizenship in participatory democracy. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(11),1611-1622.

- Notley, T., & Dezuanni, M. (2019). Advancing children’s news media literacy: Learning from the practices and experiences of young Australians. Media, Culture & Society, 41(5), 689-707.

- Notley, T., & Dezuanni, M. (2020, July 6). We live in an age of ‘fake news.’ But Australian children are not learning enough about media literacy. The Conversation.

- Wineburg. S. & McGrew. S. (2018). To avoid getting duped by fake news, think like a fact checker. Huffington Post.

- Wikimedia (2021). Croatian Wikipedia disinformation assessment-2021.

- Warzel. C. (2021, Feb. 18). Don’t go down the rabbit hole. New York Times.